Anima and Snakes in Jung’s Psyche

In my opinion, many Jungians take the writings of Jung as gospel, and do not take into account the cultural context from which he wrote. His view, for instance, of the anima and the feminine is a bit chauvanistic and confining. This article by Dr. Austin is an excellent review of the cultural context in which Jung was writing. Although I have excerpted it to facilitate reading on the Web, it is well worth the effort to read it in full.

by Dr. Sue Austin

International Journal for Jungian Studies, 2004, Vol.50, No.2

Desire, Fascination and the Other: Some Thoughts on Jung’s Interest in Rider Haggard’s ‘She’ and on the Nature of Archetypes.

In my 20s, many years prior to training with the Australian and New Zealand Society of Jungian Analysts, I read my way through the Collected Works of C.G. Jung. As I did so, I repeatedly encountered images of women – mythical, ‘archetypal’ women – and I became aware that while I was fascinated by these images, I was also profoundly uncomfortable with something about them.

…..

I would now say that as an adolescent watching the film I was looking for images which might help me work out some sort of relationship between being gendered female and questions about love, power, sex, punishment and death…

What comes through was that Jung and the first generation of his followers took works like She as raw examples of the recurrent and universal nature of certain male fantasies about womanhood.

…

I would suggest that the concept of archetype, like the myths and fairy stories that it is derived from and speaks through, is also political and that all symbols, no matter how powerful, or how apparently universal, operate as political devices which are loaded up with meaning by the process of their own culturally-based origination. In order to illustrate this, I will take up an imaginal encounter between Jung and a figure he calls Salome. This encounter took place in one of Jung’s experiments with active imagination, and Jung described it in his autobiography, Memories, Dreams, Reflections (1977, first published in 1963)… Exploring how images of these women were constituted at the time Jung was writing has helped me to understand my discomfort with Jungian discussions of ‘archetypal femininity’.

Jung writes:

I caught sight of two figures, an old man with a white beard and a beautiful young girl … The old man explained to me that he was Elijah, and that gave me a shock. But the girl staggered me even more, for she called herself Salome! She was blind … They had a black serpent living with them who displayed an unmistakable fondness for me. I stuck close to Elijah because he seemed the more reasonable of the three, and to have a clear intelligence. Of Salome I was distinctly suspicious … Soon after this fantasy another figure rose out of the unconscious. He developed out of the Elijah figure. I called him Philemon (Jung, 1977, pp.205-206).

Jung’s own response to his Salome image is given in two paragraphs (Philemon merits eleven paragraphs). She is seen as a parallel to various dancing girls and a young woman who Simon Magus ‘… picked up in a brothel’, and as an ‘… anima figure [who] is blind because she does not see the meaning of things, Elijah is the figure of the wise old prophet and represents the factor of intelligence and knowledge; Salome the erotic element. One might say that the two figures are personifications of Logos and Eros’ (Jung, 1977, p.206).

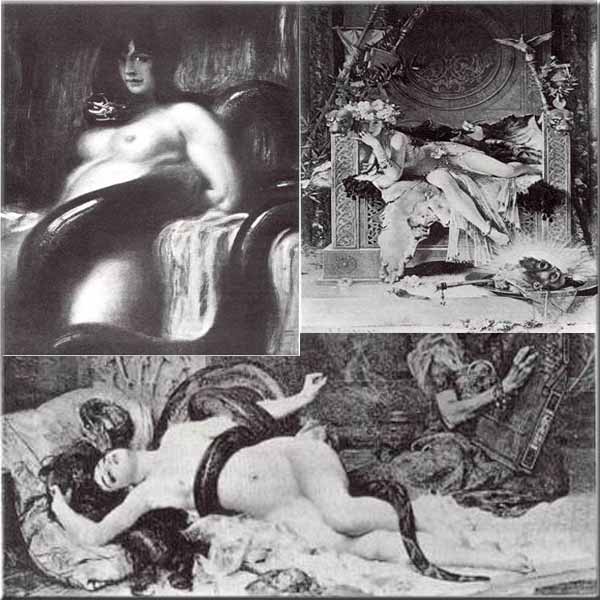

In order to put Jung’s Salome and serpent into their cultural context it is necessary to examine the art of the last two decades of the nineteenth century which shows an extraordinary number of images of women and snakes, the most common mythical contexts being Salammbô, Lilith, Ishtar and Medusa.

…..

Of particular interest is the period’s imagery of women and serpents. A plethora of images were produced including Snake Queen(s), The Scene of The Serpent, Egyptian Fantasy, and Serpentine Dancers. At a more generic level, images of Sensuality, Sin, Vice, Lust and so on were popular, frequently featuring women moving snakily, caressing or being caressed (usually ecstatically) by snakes, or with snakes forming part of their anatomy: commonly legs, thighs and loins, or hair.

These images sit against the backdrop of a general flourishing of artistic works and surprisingly immodest stories in popular magazines about women’s ‘natural’ tendency to rapidly degenerate to a bestial past and engage in intimate relationships with animals generally (snakes in particular), given half a chance.

…

I am not saying that Jung was directly influenced by these works. My point is simply that Jung worked in a particular cultural context and that certain images were not only common place in that world and carried particular significance which has since changed as the culture has changed, but that these images and their meanings were firmly embedded in cultural context

…

In the light of the foregoing texts which point to the blindingly dangerous nature of Salome’s presence, it is not surprising that she is blind in Jung’s fantasy. Given the proliferation of fin-de-siecle fantasies about women like Salome, it is also not surprising that Jung’s analysis of what she represents in his imagination does not extend to the usual Jungian understanding of blindness in myth or fairy story – that loss of external sight is associated with gains in inner-sight.

….

What goes awry when Jung discusses his internal images is that he only partially applies his own theory, with the result that he prefers to engage with the more accessible, less threatening Philemon, a ‘wise old man’, and turns away from the unsettling Salome. The issue here is that by Jung’s own theory, engaging with Salome’s unsettling Otherness might bring greater possibilities for growth, since her unsettlingness flags her as a portal to the ‘Not-I within’. As an aside, beyond Salome, there is another, even less accessible (and probably therefore even more important) portal to the ‘Not-I within’ in Jung’s fantasy…

….

As a clinician I am especially interested in these moments of inarticulate desire and resistance to identity and how they are regulated out of existence through our performance of identity, especially gendered identity. I am also interested in what people do with the kinds of canalisations of desire which constitute identity, in other words, how and where individuals (for example) variously resist, work with or capitulate to these canalisations. Likewise I am curious about how people do (or don’t) eroticise and make meaning (or fail to make meaning, or refuse to make meaning) out of their conscious and unconscious choices in these domains of identity….

(Full article)

Jung was and is clearly closer than anyone so far to an understanding of the human psyche and soul but I think he had a few issues with women. Nonetheless, his contributions are unparalelled.(where is sp. checker when you need it?) And yes his cultural influences would fit with his views…

This article is really insightful. As an intuitive working to understand the nature of the unconscious I understand Jung’s approach though it is also a limiting and constraint approach on his part. He did not explore the unconscious deeply except by what he already knew from what I read in the article, he still showed his penchant on chauvinism by only looking at the old man and not salome.

It is true as a man Jung has made much more progress than his contemporaries in the field of understanding the human psyche yet to go further and it is truly a frightening experience is to delve in the unconscious to understand the feminine principle and its relation to the snake and what is not clearly defined or tamed.

It is the nature of people to want security and to be in control and for Jung that was no different. In a way, he was not as emancipated as I would have hoped him to be, he was still working with a male perspective not objectivity in the sense of seeing fully and exploring the unconscious that way.

Of course, we all know the dangers of it if we begin a journey in the unconscious, inner life, we know it is not a world guided by external principle or rules and we must thread cautiously even there.

I do understand Jung’s approach and I also know for sure that there is much more to be discovered about it and still on the feminine aspect which not much is truly known of except for men’s anima projections on women who have not been able to free themselves for the most part from such drudgery and slavish male domination.

Great Article!!!

There is no female, no male. Duality makes it so. All have feminine and masculine in the helix. This was Jungs “masterpiece.”

To skip the “apprenticepiece” is being human and rightly so.

Until an observer can see the projections cast out on to the environment , there is little possibility of reconciling the divided male/female fallacy.