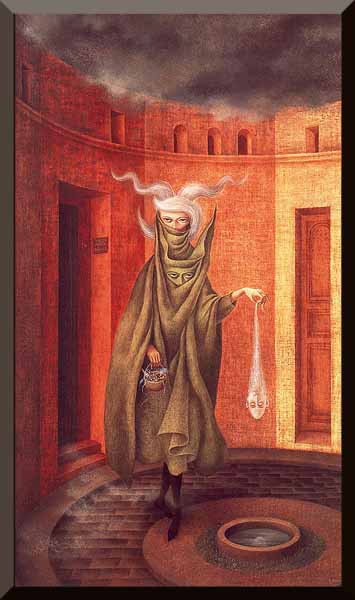

Remedios Varo: Three Paintings

Oil on canvas, 27-7/8 x 16-1/8 in.

Private collection.

From Remedios Varo: Unexpected Journeys; Janet Kaplan

Whether Varo herself ever sought psychiatric help is undocumented. Her letters to unknown psychiatrists, filled with descriptions of ridiculous imaginary crisis, and pleas for help, were surely written in jest, as was her proposal for a psychoanalytic clinic in which one could choose either to live out ones own fantasies or to work against someone elses. Yet she was known as a deeply anxious woman who harbored many fears. “I am hopelessly superstitious… so much so that when I go out, even to a nearby place, I return as quickly as possible to shut myself up in the house as if someone were following me.” As indicated in her work, Varo seems to have shared the recurring fears of women who, in peacetime as in war, face the threat of arbitrary violence. Thus her female characters tense confrontations and ominous encounters with strange men are more frightening than funny.

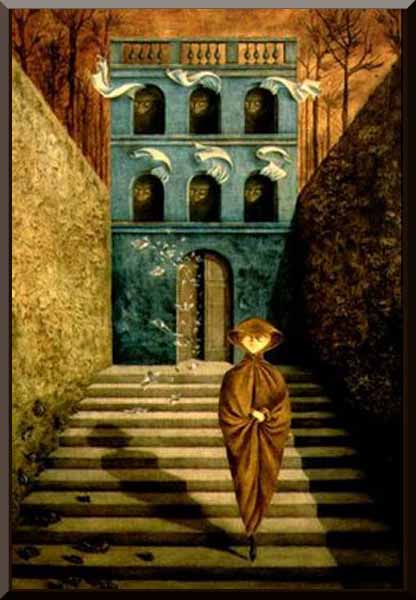

36-3/8 x 22-3/4 in.

Private collection.

From Remedios Varo: Unexpected Journeys; Janet Kaplan

Clutching her cloak protectively, the girl, so self-contained and seemingly alone, faces squarely away from the building; but her eyes have rolled up like the identical pairs of eyes that follow her every move from the buildings arched windows. These are the watchful eyes of tradition and the past from which she is making a break, the restrictive scrutiny that had prompted her to bury her childhood fantasy stories, the intrusive spying against which she had guarded her doorway with sugar. Although life in a strict Spanish family and education in a convent surely did involve numerous watchful eyes, it is also true that, for Remedios, the watching was as intensely imagined, as it was real. As her widower, Walter Gruen, has suggested, no matter how much freedom Varo might have had as a girl, she would never have felt it was enough.

Oil on Masonite, 27-7/8 x 33 in.

Private collection

From Remedios Varo: Unexpected Journeys; Janet Kaplan

A clockmaker at his bench is surrounded by grandfather clocks, each of which shows the same time but contains a figure wearing a different period costume. Suddenly, a whirling disk spins into his window and he looks up, as Varo described it, with “an expression of astonishment and illumination” to find a fundamentally new vision of how time works. The clockmaker “represents our ordinary time,” and all of his timepieces operate within the Newtonian construct of a “clockwork universe,” a system of absolutes in which the flow of time is unchanging. Thus even though the costumed figures are from different periods, the time on each of their clocks is exactly the same. The vision that has caught the clockmaker by surprise and sent his spare parts crashing to the floor represents the Einsteinian revelation that time is relative. Since each observer in each place will experience it differently, according to his won frame of reference, time is not a fixed moment to be trapped within a clock. Surely this vision must be difficult for the clockmaker to accept, for it challenges the fundamental premise of his craft.