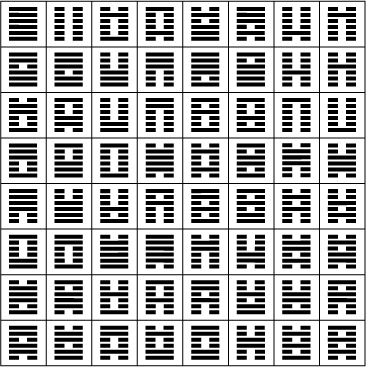

Jung writes all 64 hexagrams of the I Ching from memory…

“Sympathetic this his psychology, before they met, [Jolande Jacobi] was mesmerized afterwards when Jung wrote all sixty-four hexagrams from memory.”[1928]

I first met Richard Wilhelm at Count Keyserling’s during a meeting of the “School of Wisdom” in Darmstadt. That was in the early twenties. In 1923 we invited him to Zurich and he spoke on the I Ching (or Yi Jing) at the Psychology Club.

Even before meeting him I had been interested in Oriental philosophy, and around 1920 had begun experimenting with the I Ching. One summer in Bollingen I resolved to make an all-out attack on the riddle of this book. Instead of traditional stalks of yarrow required by the classical method, I cut myself a bunch of reeds. I would sit for hours on the ground beneath the hundred-year-old pear tree, the I Ching beside me, practicing the technique by referring the resultant oracles to one another in an interplay of questions and answers. All sorts of undeniably remarkable results emerged-meaningful connections with my own thought processes which I could not explain to myself.

The only subjective intervention in this experiment consists in the experimenter’s arbitrarily – that is, without counting-dividing up the bundle of forty-nine stalks at a single swoop. He does not know how many stalks are contained in each bundle, and yet the result depends upon their numerical relationship. All other manipulations proceed mechanically and leave no room for interference by the will. If a psychic causal connection is present at all, it can only consist in the chance division of the bundle (or, in the other method, the chance fall of the coins).

During the whole of those summer holidays I was preoccupied with the question: Are the I Ching’s answers meaningful or not? If they are, how does the connection between the psychic and the physical sequence of events come about? Time and again I encountered amazing coincidences which seemed to suggest the idea of an acausal parallelism (a synchronicity, as I later called it). So fascinated was I by these experiments that I altogether forgot to take notes, which I afterward greatly regretted. Later, however, when I often used to carry out the experiment with my patients, it became quite clear that a significant number of answers did indeed hit the mark. I remember, for example, the case of a young man with a strong mother complex. He wanted to marry, and had made the acquaintance of a seemingly suitable girl. However, he felt uncertain, fearing that under the influence of his complex he might once more find himself in the power of an overwhelming mother. I conducted the experiment with him. The text of his hexagram read: “The maiden is powerful. One should not marry such a maiden.”

In the mid-thirties I met the Chinese philosopher Hu Shi. I asked him his opinion of the I Ching, and received the reply: “Oh, that’s nothing but an old collection of magic spells, without significance.” He had had no experience with it – or so he said. Only once, he remembered, had the come across it in practice. One day on a walk with a friend, the friend had told him about his unhappy love affair. They were just passing by a Taoist temple. As a joke, he had said to his friend: “Here you can consult the oracle!” No sooner said than done. They went into the temple together and asked the priest for an I Ching oracle. But he had not the slightest faith in this nonsense.

I asked him whether the oracle had been correct. Whereupon he replied reluctantly, “Oh yes, it was, of course…” Remembering the well-known story of the “good friend” who does everything one does not wish to do oneself, I cautiously asked him whether he had not profited by this opportunity. “Yes,” he replied, “as a joke I asked a question too.”

“And did the oracle give you a sensible answer?” I asked.

He hesitated. “Oh well, yes, if you wish to put it that way.” The subject obviously made him uncomfortable.

A few years after my first experiments with the reeds, the I Ching was published with Wilhelm’s commentary. I instantly obtained the book, and found to my gratification that Wilhelm took much the same view of the meaningful connections as I had. But he knew the entire literature and could therefore fill in the gaps which had been outside my competence. When Wilhelm came to Zurich, I had the opportunity to discuss the matter with him at length, and we talked a great deal about Chinese philosophy and religion. What he told me, out of his wealth of knowledge of the Chinese mentality, clarified some of the most difficult problems that the European unconscious had posed for me. On the other hand, what I had to tell him about the results of my investigations of the unconscious caused him no little surprise; for he recognized in them things he had considered to be the exclusive possession of the Chinese philosophical tradition.

As a young man Wilhelm had gone to China in the service of a Christian mission, and there the mental world of the Orient had opened its doors wide to him. Wilhelm was a truly religious spirit, with an unclouded and farsighted view of things. He had the gift of being able to listen without bias to the revelations of a foreign mentality, and to accomplish that miracle of empathy which enabled him to make the intellectual treasures of China accessible to Europe. He was deeply influenced by Chinese culture, and once said to me, “It is a great satisfaction to me that I never baptized a single Chinese!” In spite of his Christian background, he could not help recognizing the logic and clarity of Chinese thought. “Influenced” is not quite the word to describe its effect upon him; it had overwhelmed and assimilated him. His Christian views receded into the background, but did not vanish entirely; they formed a kind of mental reservation, a moral proviso that was later to have fateful consequences.

In China he had the good fortune to meet a sage of the old school whom the revolution had driven out of the interior. This sage, Lau Nai Suan, introduced him to Chinese yoga philosophy and the psychology of the I Ching. To the collaboration of these two men we owe the edition of the I Ching with its excellent commentary. For the first time this profoundest work of the Orient was introduced to the West in a living and comprehensible fashion. I consider this publication Wilhelm’s most important work. Clear and unmistakably Western as his mentality was, in his I Ching commentary he manifested a degree of adaptation to Chinese psychology which is altogether unmatched.

When the last page of the translation was finished and the first printer’s proofs were coming in, the old master Lau Nai Suan died. It was as if his work were completed and he had delivered the last message of the old, dying China to Europe. And Wilhelm had been the perfect disciple, a fulfillment of the wish-dream of the sage.

My amazement with Jung never ceases. While I have read everything I could by him and, with reserve, things about him but only that based upon personal familiarity with the man himself. Many, especially during the height of the woman’s movement, labeled him a sexist, although his translators and Jung himself noted certain translation problems between Swiss/German and English. He also adds in his own text that he had lived his life as a man and had little insight to his unconscious feminine side. Once he quipped, “If someone else had written this work, it would have come out different.”

So cool! In Zhou Yi Dao our ‘entrance exam is to write out the 64 hexagrams from memory.