Mary Bancroft: Patient and Spy

” I thought Jung should tell me what to do. Whether I should write a book, or I should get a divorce, what I should do. And he wouldn’t. And so I got mad at him.

And I said, “Why is everybody so mean to me?” And he said, “Why are you so mean to everybody?” So I stormed out. You got what I said there. I said to him, “Why is everybody so mean to me?” and he said, “Why are you so mean to everybody?” That was the trigger.

I was gone for a year. And I wrote, oh, I don’t know, every now and then I’d sit down at the typewriter and write what a son of a bitch I thought he was. How when I first got to Europe everyone thought he was a charlatan, I thought he was, too. He was the most conceited, vain man. You know, I really had a great time.

[Interviewer: “And you sent all these letters?”] Sent the letters. Of course I did. And I thought, I hope he drops dead of a stroke. And I felt very good. I just felt fine. When I can get mad I can lose five pounds, just by getting mad. The adrenalin goes… You know it’s the opposite of “poor little me.” I don’t care; let the world go stuff it up…I don’t care what happens.

And then one morning I woke up and I began to laugh. For God’s sake, what’s been going on here? What a jackass you… And suddenly I realized, surely, he really hit it. And so I phoned Miss Schmidt, Frau Schmidt, and I asked if I could have an appointment. And she laughed and said, “O, yes,” she said, “Professor Jung told me to save some time for you. He thought you’d be calling shortly.””

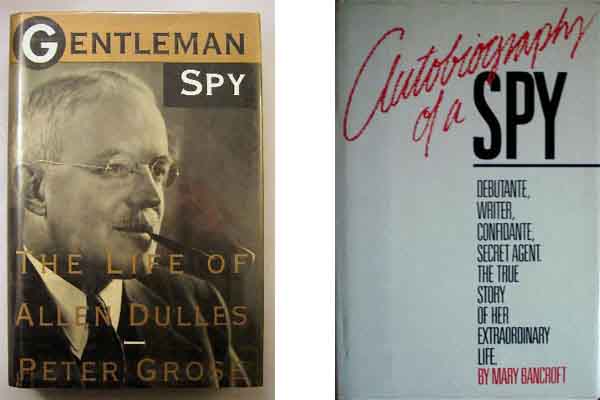

Mary Bancroft recruited Jung to be a spy in WWII. Seriously. (More about this on the next post.) Her story is told in “Autobiography of a Spy.” Here is good summary of her life:

Obituary: Mary Bancroft)

Godfrey Hodgson

Monday,

17 February 1997

Mary Bancroft was that rarity in real life, a glamorous upper- class spy. She reached that condition by the tried and tested method of having a love affair with a man who was himself one of the most important spies of the Second World War and went on to be the most celebrated chief of America’s Central Intelligence agency.

Allen Welsh Dulles had served as an American secret agent in Switzerland during the First World War. After the United States joined the Second World War, Colonel “Wild Bill” Donovan, head of the Office of Strategic Services, precursor of the CIA, gave Dulles the assignment of returning to Switzerland to create a network of intelligence inside Nazi Germany.

Dulles sent an NBC radio technician, Gerald Mayer, ahead to begin identifying possible agents, and one of the first people Mayer recruited was Mary Bancroft.

Then a handsome, bored married woman aged 38, Mary Bancroft had dropped out of Smith College in Massachusetts, and rebelled against the ultra- respectable life of a debutante in Beacon Hill, the Mayfair of Boston, where she was brought up by her stepgrandfather, C.W. Barron, who was the publisher of the Wall Street Journal and the founder of the business magazine which bears his name. Something of a Bright Young Thing, not to say a “goer”, in the Jazz Age, Bancroft had been married twice, first to an American, then, to the surprise of her friends, to a Swiss accountant called Jean Rufenacht. She tired of the marriage, and first wrote a novel, then began to study the work of the great Swiss psychologist, Carl Gustav Jung.

She had many lovers, and as her husband’s work took him away from home frequently, she was in restless and emotionally available mood – “randy and ready”, says Dulles’s biographer – when, early in December 1942, she was introduced to Allen Dulles over a drink at the ultra-discreet Hotel Baur am Lac in Zurich. Her upper-class credentials appealed to Dulles, himself the nephew and grandson (and later the brother) of American Secretaries of State, and a partner in the powerful New York law firm, Sullivan & Cromwell. But she was also a highly intelligent woman who had been living in Switzerland since 1934 and had acquired excellent French and German.

He quickly put the relationship on a more intimate basis by asking her to help him to find some bed-linen, scarce in wartime Bern, where he lived under diplomatic cover, and she obliged by lending him some from her husband’s country chalet.

Within days he took her for a walk along the lake in Zurich and put his double proposition to her with bluntness close to effrontery. “We can let the work cover the romance,” he said, “and the romance cover the work.”

Before long both work and romance had settled into an efficient and pleasurable routine. Every morning, at precisely 9.20, Dulles would telephone Bancroft and tell her what reports he needed translated. They kept their conversation secure by using American slang, something that was more impenetrable in Switzerland in 1943 than it would be today.

Once a week she would take the train from Zurich to Bern, and check in at a cheap hotel opposite the station. She would then take a taxi to Dulles’s comfortable home, where they would spend the day preparing a report for Washington. That evening Dulles would report to Donovan over a more or less secure radio-telephone, high technology for the day. Spy master and spy mistress would then retire to bed together.

After a while, Dulles gave Bancroft the assignment of editing a book written by Hans Bernd Gisevius, an upper-class Prussian military intelligence officer who was both an agent of Admiral Canaris’s Abwehr secret intelligence service, and a member of the anti-Nazi underground. He was naturally one of Dulles’s most prized contacts inside the German Resistance. Before long, Mary was romantically involved with Gisevius too.

At the same time as she was becoming drawn deep into the web of intelligence- gathering and anti-Nazi plotting in Switzerland, Bancroft was getting more and more involved in her study of Jungian psychology, and eventually became a confidante of Jung himself.

Her relationship with Dulles soon began to cool; he was a physically ardent but emotionally cold lover who once demanded that they make love hastily on a sofa “to clear his head” before an important meeting. After the end of the war, Dulles was joined in Switzerland by his wife Clover. She lost no time in telling Bancroft that she was aware of her relationship with her husband and that she approved of it, and the two women became close friends for life.

Later, after Dulles had become the first head of the new Central Intelligence Agency and she had returned to New York, Bancroft also became close, though apparently not sexually involved with, Henry Luce, the publisher of Time and Life, whose wife, Clare Booth Luce, was another of Allen Dulles’s lovers. She became a leading champion of Jung’s psychology in the United States and wrote a number of articles in learned journals about his work.

The relationship with the Dulles family became even closer when, in 1952, Bancroft’s daughter, Mary Jane, married Horace Taft, son of the conservative candidate for the Republican presidential nomination, and Allen Dulles gave the bride away.

In 1983 Mary Bancroft wrote her memoirs, which she called Autobiography of a Spy.

Godfrey Hodgson